Montgomery教授所著的”Introduction to Statistical Quality Control”書中提到一個觀念,此觀念涉及到業界常常會遇到的品質系統及其相關活動,例如稽核、認證、訓練等等;Montgomery教授認為這些要求品質的活動與真正的品質改善關聯不大,甚至認為這些活動只是浪費金錢,做出一堆沒有貢獻的系統,而非真正改善品質。

他認為改善品質真正的關鍵在於降低變異(Reducing variability),可想而知這觀念與我們現在常見的品質稽核、品質系統導入和品質文件有多大的不同。我們總是認為要改善品質就要導入ISO品質系統,先從品質目標開始做起,然後建立四階文件、設立流程、導入顧問公司、內部稽核外部稽核、取得認證;再不斷要求文件管理、變更管理、追朔性、風險管理、產品設計開發管制等文件證據。

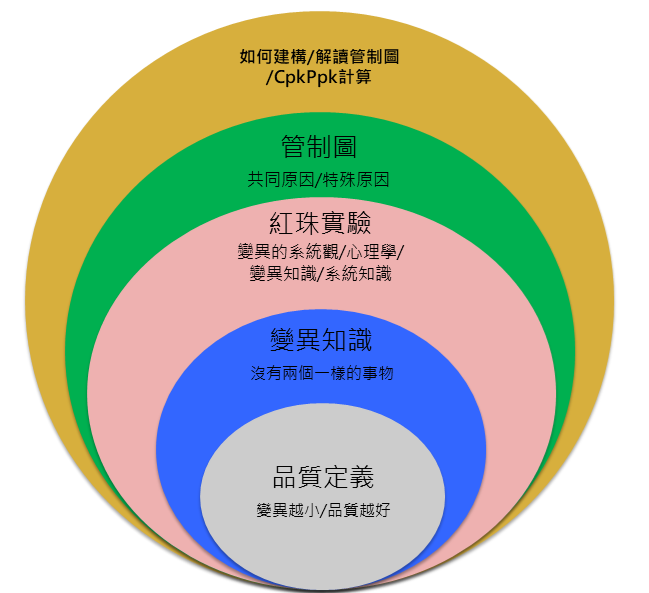

但是真正改善品質並不是導入一個系統或者工具,反倒是在觀念上要能接受「品質就是降低變異」的先決條件,掌握住品質不良的根本原因在於變異過大,然後了解變異的來源有兩種:一種來自於可預料的、環境系統層面的共同原因,這要管理階層出面處理 佔了85%;一種來自於機遇性、無法預料的特殊原因,僅佔15%。

在擁有了這些變異知識、系統知識、知識體系以及心理學理論之後,整家公司才能藉由這些體系形成的架構,往下延伸到各個部門主管再持續扎根,否則我們對於品質就只是做些表面功夫,永遠不可能達到高水準的品質。

下列段落節錄於Introduction to Statistical Quality Control 6th Edition

網路上便搜尋得到 應該沒有版權問題

Many organizations have required their suppliers to become certified under ISO 9000, or one of the standards that are more industry-specific. Examples of these industry-specific quality system standards are AS 9100 for the aerospace industry; ISO/TS 16949 and QS 9000 for the automotive industry; and TL 9000 for the telecommunications industry. Many components of these standards are very similar to those of ISO 9000.

Much of the focus of ISO 9000 (and of the industry-specific standards) is on formal documentation

of the quality system; that is, on quality assurance activities. Organizations usually must make extensive efforts to bring their documentation into line with the requirements of the standards; this is the Achilles’ heel of ISO 9000 and other related or derivative standards. There is far too much effort devoted to documentation, paperwork, and bookkeeping and not nearly enough to actually reducing variability and improving processes and products. Furthermore, many of the third-party registrars, auditors, and consultants that work in this area are not sufficiently educated or experienced enough in the technical tools required for quality improvement or how these tools should be deployed. They are all too often unaware of what constitutes modern engineering and statistical practice, and usually are familiar with only the most elementary techniques. Therefore, they concentrate largely on the documentation, record keeping, and paperwork aspects of certification.

There is also evidence that ISO certification or certification under one of the other industry-specific standards does little to prevent poor quality products from being designed, manufactured, and delivered to the customer. For example, in 1999–2000, there were numerous incidents of rollover accidents involving Ford Explorer vehicles equipped with Bridgestone/Firestone tires. There were nearly 300 deaths in the United States alone attributed to these accidents, which led to a recall by Bridgestone/Firestone of approximately 6.5 million tires. Apparently, many of the tires involved in these incidents were manufactured at the Bridgestone/Firestone plant in Decatur, Illinois. In an article on this story in Time magazine (September 18, 2000), there was a photograph (p. 38) of the sign at the entrance of the Decatur plant which stated that the plant was “QS 9000 Certified” and “ISO 14001 Certified” (ISO 14001 is an environmental standard).

Although the assignable causes underlying these incidents have not been fully discovered, there are clear indicators that despite quality systems certification, Bridgestone/Firestone experienced significant quality problems. ISO certification alone is no guarantee that good quality products are being designed, manufactured, and delivered to the customer. Relying on ISO certification is a strategic management mistake. It has been estimated that ISO certification activities are approximately a $40 billion annual business, worldwide. Much of this money flows to the registrars, auditors, and consultants. This amount does not include all of the internal costs incurred by organizations to achieve registration, such as the thousands of hours of engineering and management effort, travel, internal training, and internal auditing. It is not clear whether any significant fraction of this expenditure has made its way to the bottom line of the registered organizations. Furthermore, there is no assurance that certification has any real impact on quality (as in the Bridgestone/ Firestone tire incidents). Many quality engineering authorities believe that ISO certification is largely a waste of effort. Often, organizations would be far better off to “just say no to ISO” and spend a small fraction of that $40 billion on their quality systems and another larger fraction on meaningful variability reduction efforts, develop their own internal (or perhaps industry-based) quality standards, rigorously enforce them, and pocket the difference.

瀏覽次數: 10